Companies employing motorsport experts to produce green Porsches and Rolls-Royces at a cost of up to £500,000 are starting to attract investors

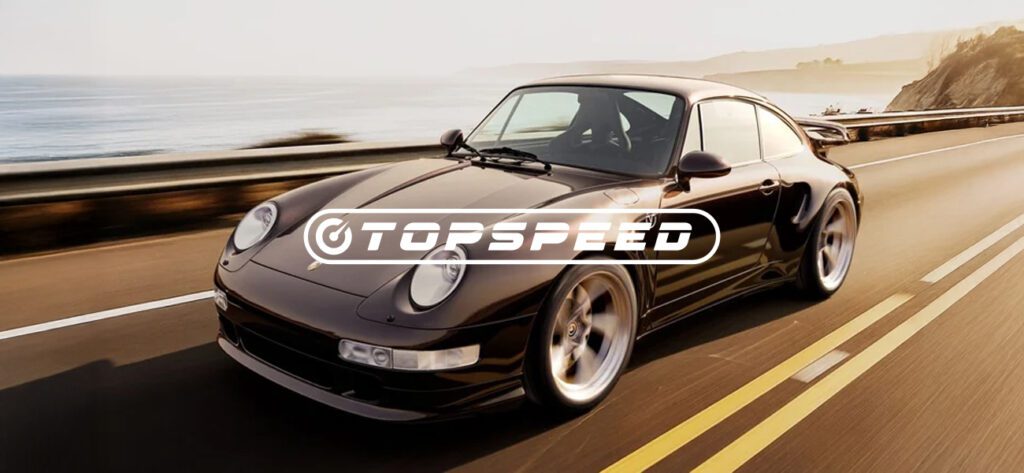

The acceleration is relentless, the handling crisp, the feel through the steering wheel among the best. The only thing missing is the distinctive engine noise of one of the greatest cars of all time: the 1991 Porsche Carrera 911 “964”.

Read the full article by Iain Macauley on The Times website.