Land Rovers have tackled the Sahara and towed howitzers. But the most surprising thing about this truck, as with a growing cohort of sought-after classic cars? It’s electric.

The sound doesn’t match the picture. I’m driving a Porsche 911 of late 1980s vintage. Arrayed before me are its five big, clear analogue driving dials, visible through the simple three-spoke wheel. The windscreen is upright for a sports car by modern standards, and the thin roof pillars let light flood in but would buckle fast in a rollover. Beyond the screen, the two long steel cannons bearing the headlights point directly down the closed runway, the car’s sloping hood slung low between them.

So far, so Porsche. But the guttural, unfiltered rattle-rasp of the air-cooled engine beloved by Porsche purists and central to an old 911’s appeal is entirely absent. Instead, there’s just a low, constant background whirr. It doesn’t increase much when I bury the throttle, but the speed does, exponentially. This old car suddenly leaps forward 30 years, accelerating as quickly as the fastest Tesla—and too fast for your brain to process the torrent of visual information now being streamed at it. You just have to remind yourself that the runway was clear before you hit the “gas” and keep your foot to the floor for as long as you dare. It’s hilarious, frightening and deeply strange to anyone familiar with old Porsches: a 20th-century view with 21st-century noise and performance.

How does this incongruity make you feel? Some consider the idea of a desirable, collectable, important classic car having its engine stripped out and replaced with an electric motor as progress; others as sacrilege. Some see classic cars as art and as inappropriate to modify as the Mona Lisa. Others view them as more akin to architecture: beautiful but functional and in need of occasional rewiring and replumbing to suit the expectations of modern users. As one collector told me, you wouldn’t live in a fine Georgian house and still throw your sewage out the window.

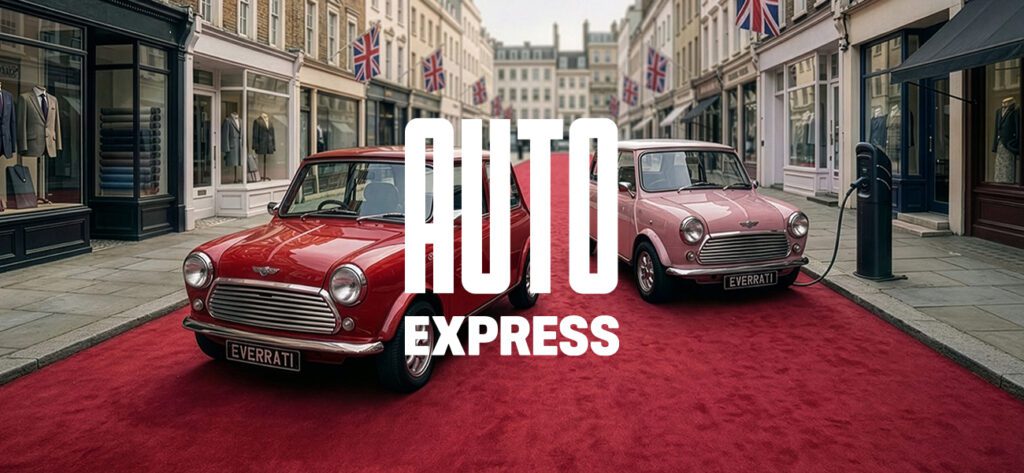

The debate engendered by models like this Everrati 911 (above) is polarizing the classic-car world. Every social-media post featuring one attracts a slew of critics grousing, perhaps not unreasonably, that the engine is the heart of the automobile and that its removal diminishes the car’s appeal—not to mention depletes the remaining stock of a significant, historic model. One classic-car-world figure Robb Report spoke to said he wouldn’t buy an electric vehicle until forced to by legislation. Another said he wished companies in the vein of Everrati, producing electric classics, would just leave old cars alone.

Others clearly differ. Even with prices starting at about $310,000 (all prices at current exchange rates), including the donor car, you’ll wait 11 months just to get a build slot for an Everrati 911 and anywhere from seven to 14 months for the three other models it offers. At its rival Lunaz, based just 20 miles away at the UK’s Silverstone Grand Prix circuit, the wait is close to two years, despite production capacity for about a hundred cars per annum and prices that start at around $335,000 for an electrified classic Range Rover and extend well north of $1 million for a restored and converted Aston Martin DB6, including the donor car. Lunaz has taken investment from David Beckham, Oculus founder Brendan Iribe and the Barclay and Reuben families, two of Britain’s wealthiest, and it has already declined an opportunity to go public.

I’m basically a recovering petrolhead,” says Everrati’s 51-year-old British cofounder, Justin Lunny. The serial fintech entrepreneur sold a business in 2016 and was looking for something to do next. “When I was 8, all I could think about were cars. But my daughter was a similar age when I exited that business, and she was genuinely worried about the Earth flooding. As a dad, that’s pretty scary. So, getting into something that involved both clean tech and cars was perfect. I know I’m not going to be the next Elon Musk, but it’s good to think you’re making a difference.”

Lunny found a ready market for his EV conversions among fellow tech entrepreneurs. Everrati’s first US customer was Matt Rogers, the 39-year-old cofounder of Nest, which Google acquired in 2014 for $3.2 billion. He’s now an Everrati investor and is already specifying his second electric 911.

“I went to see him to ask why he bought a car from a little start-up in rural England,” Lunny says. “Matt’s dad had the same model of 911, and he basically grew up in the back seat. He’d always promised himself one, but it had to be electric.”

Everrati operates almost virtually, outsourcing the restoration of the entire car (bar the engine, of course) to established marque specialists and acquiring the electric drivetrain components from the best suppliers, which are often local. Its value lies in how well it integrates the two and in how easily the electric drivetrain developed for, say, a Mercedes-Benz Pagoda—its forthcoming conversion model—can be adapted to fit another classic car with the same front-engine, rear-wheel-drive layout, either as a regular model in the Everrati range or as a one-off conversion of a customer’s existing car.

“There is a huge transference of wealth between generations coming, and that includes some vast car collections,” says Lunny. “The millennials inheriting these cars might not drive them if they have combustion engines, but we can convert them and help them continue to use them.”

Matt’s dad would feel at home in his son’s electric 911. The restoration is carried out by the Aria Group, which also produces Singer’s feted restomod 911s and builds concept cars for the major manufacturers. Mad electric thrust aside, it still drives like a 911, because it still is a 911. The center of gravity and weight distribution are pretty much the same, and the mass is only slightly less despite the weight of the batteries. The brakes and suspension have been subtly upgraded to cope with the extra pace, but in an entirely Porsche way. The 911’s edgy, rear-engine-plus-rear-drive dynamics are still there, as is the serious, deliberate heft of the steering and pedals. For me, the crazy pace compensated for the lack of noise and allowed me to enjoy more of the chassis’s talent, more of the time. The only thing I missed was the physical involvement of changing gears myself, but with so much torque available instantly from the electric motor, there’s just no need.

I loved it. You might not. But it’s harder to argue with an electric conversion of a classic car whose engine was never part of its appeal. Early Land Rovers, with their boxy, minimalist aesthetic and utilitarian credibility, are now hugely cool. But spewing particulate matter from the exhaust of a weedy, wheezy four-cylinder engine outside your kids’ school isn’t. The same goes for fighting a gearchange so vague you have no idea whether you’re in first, reverse or neutral while shoppers along London’s tony Kings Road look on. Land Rovers were always intended to be modified, and a reliable, easy-to-drive, emissions-free EV conversion in a perfectly restored body that you can use with the roof off and windshield flipped forward is deeply appealing. Everrati even leaves the Land Rover’s famous off-road hardware untouched should you want to go dune-bashing at the beach house.

Lunny says he tries to preserve the soul of these cars, and in both cases I think he has, though he might have tried less assiduously to preserve the Land Rover’s famously bouncy ride. It steers and stops far better than any other example I’ve driven, and my only reservation is the price: Can a simple farm vehicle that cost just £450, or roughly $2,000, when it was first launched in 1947 really justify a $185,000 price tag, plus the cost of the donor car, now?